Mustang’s Apples on the Move

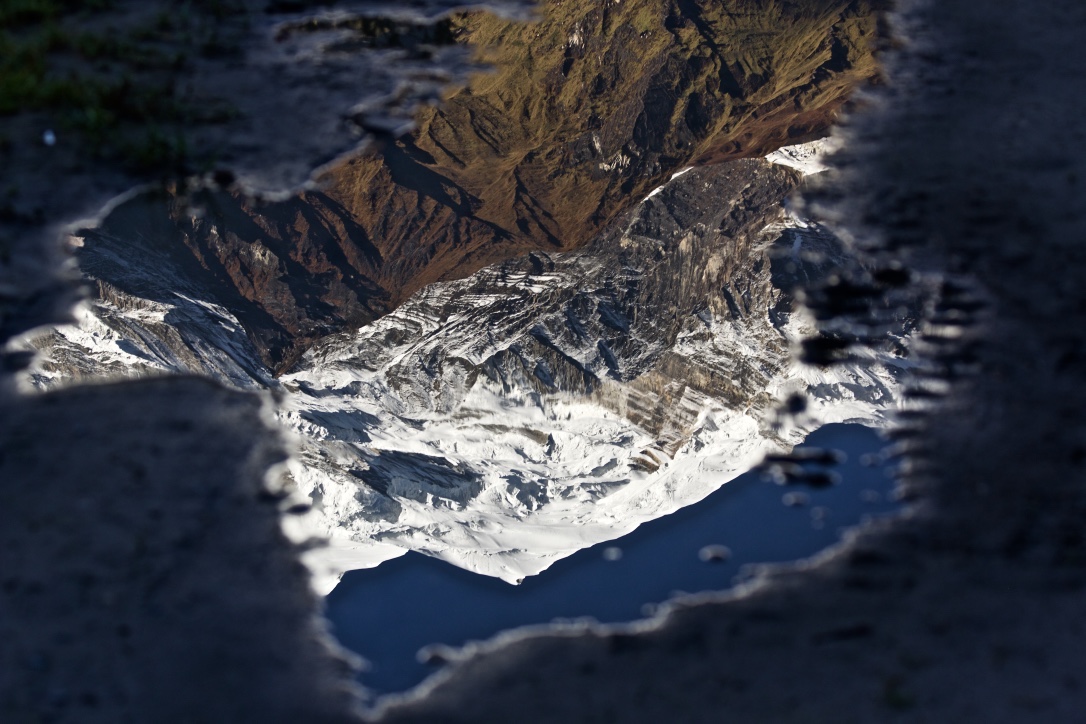

Surrounded by some of the highest peaks in the world, the Kali Gandaki river originates from Himalayan glaciers in the desert-dry region of Mustang, at the border with Tibet. Despite the arid landscape, apples have for decades been a key source of livelihood for communities in the southern part of the district, relying on snow levels to irrigate the soils during the dry season. But today, warming temperatures and melting snows are threatening apples, and the communities relying on them. Their production is moving further north, seeking for higher altitudes. This prompts the question: who wins and who loses as the climate changes, altering livelihoods in the shadow of these towering giants?